Misshapen spires of cumulonimbus clouds plopped randomly across the moon-lit sky lurked like sullen sentries in our path. “Squalls,” mumbled the skipper of the Santa Cruz 50, a fiberglass missile of a sailboat which had been my home since leaving the security of California’s coast for one of yachting’s most storied races. Pondering those ominous silhouettes, I remember thinking: “I’m 1,000 miles from shore.”

I’d first heard of the Transpac a few months earlier when I joined my brother and that same skipper, my brother’s step-son and his fiancé, and some ringer named Brian for the 125-mile Newport Beach, CA, to Ensenada, MX, race: a roughly 24-hour event neatly named the N2E. My brother’s boat back then was a One Design 35, a surfboardish sort of affair notable, if in no other way, for its inability to yield a sleepable surface anywhere along its 35-foot length.

The Transpac was an altogether different race with an altogether different crew. Spanning 10 days and 2,225 miles, the Transpac is as close to professional sailing as a recreational sailor is likely to get without owning the boat. A potentially dangerous endurance test which Hooper listed among his qualifications to get aboard Capt. Quint’s “Orca” in the movie “Jaws”. Real tough-guy stuff that made it onto “Outside” magazine’s list of “50 things to do before you die”.

Being a lover of the open ocean since my shark-fishing days, I dreamed of once again communing with the denizens of the deep so I jumped at the invitation. Getting my wife to sign-off meant promising away many a long fall weekend hiking the Appalachian Trail, but come July 4, I’m cruising Long Beach Harbor in the Santa Cruz, shaking-out a brand-new inventory of sails better measured in acres than square feet. I know, it’s a hard life, but someone’s got to live it.

What followed was a hard life. Every 24 hours of the race was chopped into “watches” where either of the two crews comprising our nine-man team sailed the boat. While on watch I assumed the only task on the boat that I excelled at, an aptly named assignment called grinding which involved straddling an 8-inch-wide fiberglass bulkhead and “grinding” a winch which tightened or loosened the spinnaker, a sail that acts more or less as the boat’s gas pedal.

This description of grinding is a gross over-simplification of a task that, executed properly, pushes the boat to its limits while avoiding life-threatening catastrophe, which is pretty much the modern day Transpac’s modus operandi.

Numerous nuances to successful grinding were alternately whispered or yelled at me by my three other watch mates: upper-middle-aged men from all walks of life whose only common thread is decades of open-ocean racing.

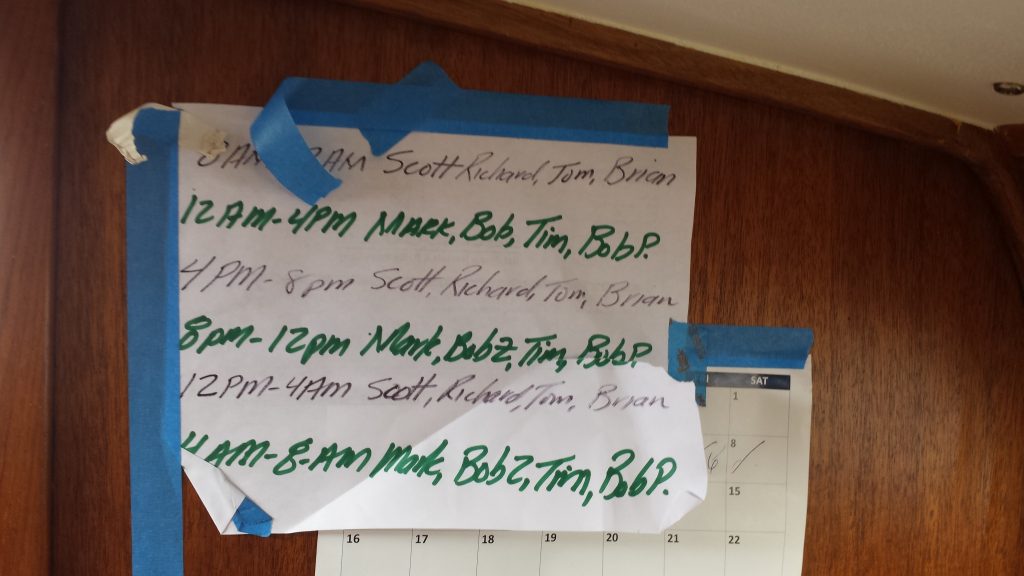

Each watch was exhausting in every way human endurance can be tested and you sat watch every other three or four hours depending on if it was day or night—a distinction that completely escaped the skipper, who was also the head of my watch.

So, between fitful naps that sent my circadian rhythms into a tailspin, I could be found grinding my ass off to a chorus of derisive voices poised to pounce on any mistake a second or so before it could be made. The one or two times I took the helm, that same chorus grew deafening sending the boat anywhere but straight as my watch mates all seemed to have different approaches to the same tasks.

At 58 years old I found myself a very poor match for this mental and physical abuse. If a little reluctance curdled in me the requisite enthusiasm expected of every Transpac crew member, the skipper picked up on it immediately and I was guilty as charged a little more than I’d like to admit.

Yet quitting was not an option as it would no-doubt mean finishing out the race enduring vastly intensified derision from the skipper and my watch mates, who through deed or dictate reminded me at every available opportunity that I was the worst sailor on the boat, despite my decades of recreational experience. So, I latched onto grinding, one of the more physically demanding tasks on the boat, as an easy means of proving my competence to my watch and shutting them the hell up in the process.

The Transpac, it turns out, does not accept mere competence. It demands enthusiasm, all too rabidly displayed by my younger brother who also signed up for the race and has his own fiberglass missile on the east coast. My occasional, ever-so-slight indifference made me the laggard of my crew while my younger brother’s effervescence made him the darling of his, adding an extra layer of irritant as I listened from my shoulder-width berth below-decks to what a grand time he seemed to be having whenever he was on watch.

These misfit feelings lasted until Day 5. Up to then my crew-mates spoke vaguely about squalls, either to frighten or avoid frightening those with less experience with same: true intent was hard to gauge with those guys. Now it would seem to me that, sitting in the middle of the world’s largest ocean in a 50-foot boat, anything called a squall should be avoided at all costs.

Far from avoiding squalls, the present day Transpac sentiment is that the added energy is not to be squandered by so-sober an act as taking down a few acres of sails. Certainly not for this skipper, unbeknownst to me as I extruded myself feet-first from my berth in the back of the boat to answer the call to the 11pm to 2am watch on Day 5-6.

I latched myself to the boat’s lifeline and immediately started grinding. The wind was around 21 knots, but clearly “freshening,” to use the sort of misnomer often employed by my watch-mates to hide the many real dangers so easy to find in an open-ocean race where survival is secondary to winning. Within minutes the wind reached sustained speeds of 26 knots. That’s 29.92 mph.

What the heck. Let’s call it 30 mph. For those not familiar with the acute sense of vulnerability found only on a perch four feet above sea-level in the middle of the night, in the middle of the ocean and charging into a storm of unknown magnitude, gusts are not the same as sustained winds. Gusts end.

The previous 4 days of the Transpac treated us to perfect, sustained winds in the low 20s that kept the boat cruising at a brisk 13 to 14 knots. Gusts occasionally edging higher allowed the fore-mentioned ringer to surf a fortuitous following sea to clock the boat’s top race speed of just over 20 knots.

Experiencing 16,000 pounds of boat “ripping”, to quote the skipper, across 6- to 8-foot ocean waves, propelled by sails obscuring your view from ear to ear is thrilling. Particularly when it’s just for a half minute or so in broad daylight.

There are certainly a few other human responses to experiencing the same for half an hour, at night, with no idea when or if it will end, or if even more “freshening” is around the corner. I might add here that, we were well beyond any rescue helicopter’s range.

On the night of my first squall, my response came down somewhere between dread and exhausted resignation as I snapped my life vest to the life line and the boat settled into a sustained speed of 15 knots breaking into 17 knots every other minute or so as the gusts crept over 30 knots.

Oh. I forgot to mention the rudder. On Day 3 of Transpac 2017, a disquieting thudding I reported to the skipper on Day 2 turned out to be the rudder and damaged bushings therein which help control the boat reliably under periods of extreme stress, such as a 26-knot squall. (In defense of the skipper, there were all sorts of noises emanating from the bowels of that boat. He didn’t take me seriously at any other point in the race, there’s no reason to fault him for not doing so at that time.)

Below decks, these bushings were about 3-feet from the head of my birth and as we got further offshore, what little sleep I got was despite the thudding. Think of Edgar Allen Poe’s, “Tell Tale Heart”. As I took to my post at the start of the squall, despite the roar of wind and rushing water, all I could hear were those occasional thuds. Were they getting louder? More frequent?

But about 5 minutes into the squall something happened that now has me seriously thinking all this suffering was not for naught. Through a laser focus on my near continuous grinding, I became one with the Saran wrap of spinnaker stretching forward ahead of the bow.

I pulled it back from the brink of collapse to grasp the entirety of available energy without losing the half second or so it took to cue the cockpit chorus. At that moment, in that squall, I became an indispensable part of a team ripping the boat through a really hairy stretch. At night.

This is an experience that is hard to describe but I derived enormous satisfaction from it. Finally, I felt on a par with my maniac crew-mates. More such moments followed. Most notably when we entered a Cuisinart of cross currents called the Molokai Channel shortly after sunset and about two hours before the finish line.

For this crucial stage of the race, the skipper promoted me to trimming the spinnaker, which is sort of the opposite of grinding. My younger brother—who was on deck for the finish—had that job, while my older brother was given the helm.

Rather than risk fraternal discord comparing sailing skills across crew members, it’s certainly accurate to say the three of us were among the least experienced open-ocean racers on the boat. The skipper’s assigning the three of us to take the boat across the finish line was one of a few flashes of cortical-level thought he exhibited that still earns him my grudging respect.

As we entered this blackhole of unseen nautical challenges, all I wanted to do was get past the finish line safe and sound. Once again, the skipper and I didn’t see eye to eye. All he did was whisper—5 inches from my ear—“keeping pushing” the spinnaker out while telling me to make sure I “don’t blow it up.” Finish line or no, I wasn’t too keen on the former command out of total dread of the latter result.

Nonetheless, the three of us executed flawlessly and his exhortations that night got us over the finish in 10 days, 12 hours, 21 minutes and 55 seconds, probably several minutes sooner than if we’d just coasted comfortably through the Molokai Channel, as I so dearly wanted to do.

As it turns out, those minutes helped propels us from seventh to sixth place in arguably one of the most competitive classes in the race. Not bad for a crew that spent a total of three hours sailing together the day before the start of the race.

Now, I’ve enjoyed similar exhilaration and feelings of accomplishment in much less trying circumstance. Many of them hiking 1,000 or so miles of the Appalachian Trail with my wife, an activity I suspect I’ll be doing a lot more of should I start formulating arguments for another Transpac. I’ve also experienced equally white-knuckled thrills day sailing.

The thing about the Transpac is this: Outside of a war zone, you will never get such a disparate group of middle-aged men to work so closely together. And I mean closely. As admittedly the least experienced racer on the boat, being able to take and keep my place among them is something I’ll look back on fondly for the rest of my life.

So, despite my vows after the race, and all the chest-beating and condescension during, I’ll consider another Transpac if the invitation is offered. I just hope this essay hasn’t significantly increased my chances of going overboard in the middle of a squall, in the middle of the night, 1,000 miles from shore. Then again, at least I will have died having crewed a Transpac.

Hello Tim, what an adventure. Thank you for sharing your story. All our best Paul and Stephanie Finnican

Tim, I this exactly what I know you are capable of doing. Thanks for sharing!

That’s about the nicest thing someone has said to me for the past 20 years or so. Glad you enjoyed it Barb. I hope all is well.